We have a worldwide ‘obesity crisis’. Everyone knows this; obesity is in the news almost every week for one reason or another, but what we seem less sure of is exactly how to address it. Whilst there are countless gadgets and apps and diet plans out there to help people lose weight, they will all lie gathering dust under a sofa unless we try to understand why obesity seems to have become such a loaded word.

Understanding the audience

For any campaign addressing obesity to be effective, the first thing to remember is who you are actually talking to.

Data showing how much obesity-related health issues cost the NHS might be perfect for engaging UK journalists who love a shocking headline, and it might get you blanket coverage in national media, but do those headlines actually engage people who are obese?

To understand how to address obesity, we need to understand why people are obese, and what their barriers are to losing weight. A new report from the British Psychological Society (BPS) explains that obesity is not a choice or a lack of willpower, and that environment and psychological experiences play a big role. Simply telling people they should lose weight isn’t going to cut it.

Why has the obesity conversation become so loaded?

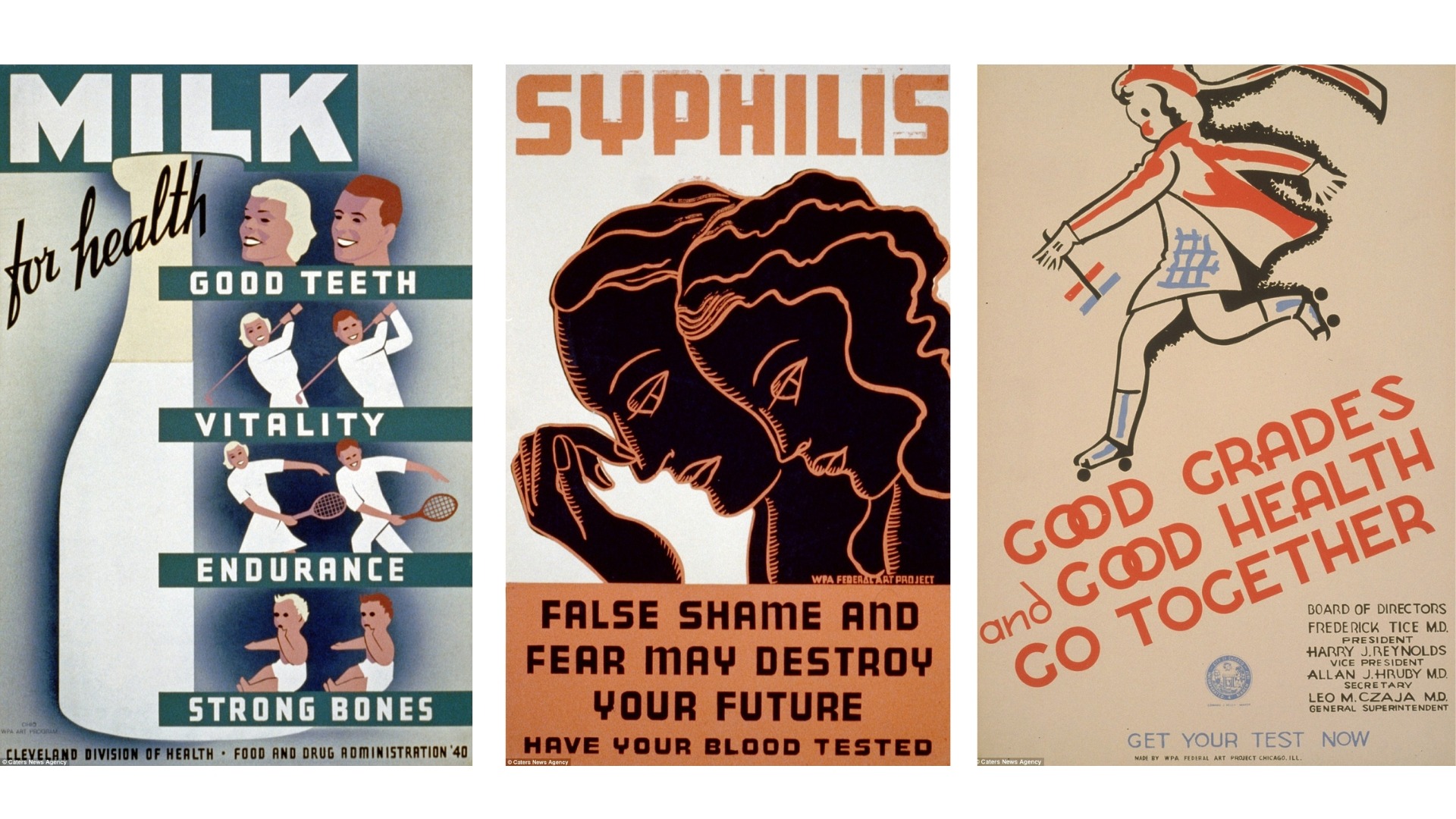

A significant part of the challenge is that the language used to convey messages about health risks is often negative and stigmatising, and clashes starkly with the equally important body positivity movement. Even the phrase ‘obesity crisis’ is instantly negative.

When Cancer Research UK ran their campaign about obesity taking over smoking as the leading cause of cancer, they were accused of ‘fat-shaming’. However, this didn’t just come from body positivity campaigners – academics and nutritionists from respected institutions also warned in an open letter that the campaign may make people with obesity too embarrassed about their weight to seek medical help.

With some tabloids choosing to run headlines like ‘Free fattie fitbits’ (about the NHS funding Fitbits for people at risk of diabetes), it’s not hard to understand why some people feel that saying ‘obesity is bad for your health’ is the same as saying ‘if you are obese you are bad’.

With other headlines like ‘Obese mothers double child’s risk of diabetes’ and ‘Fat?shaming apologies? We should be saying sorry to the NHS instead’, it’s also clear that fat-shaming is a much deeper issue than making people feel ashamed of looking fat. It’s making people feel like a burden or like they are in some way ‘bad people’ just because they are obese. This can have a devastating effect on a person’s self-worth, which in turn affects their motivation to change anything.

Addressing the stigma

The problem is, obesity’s health risks have become tangled up with society’s assumptions about people with obesity and perceptions of their appearance. Therefore, to effectively communicate the health benefits of losing weight to people with obesity, we need to de-stigmatise and work to separate the health aspect from the visual and personal aspect.

Good communication isn’t just about what you say, it’s also about listening. The glaringly obvious first step is to listen to what people with obesity say about how they want to be talked to. Anyone working in comms knows that if your messaging alienates your audience by making them feel defensive or offended, then they won’t even get as far as seeing your call to action, let alone doing it.

There are hundreds of incredible body-positivity advocates leading the way in how to speak positively about being bigger, many of whom have had their own experiences with disordered eating made worse by being made to feel like they should be ashamed of their size. Layla Moran wrote an excellent article in the Guardian about her own experiences, discussing how even the images used in news reports about obesity can be shaming.

Despite what some people like to claim, acknowledging that people who are obese are beautiful or confident is not ‘promoting obesity’, it is separating the health implications from the social stigma.

What’s the answer?

It’s not an easy challenge. On the one hand, being obese does put you at higher risk of serious health conditions such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease and cancer, and it’s important that people are informed of this and supported to make lifestyle choices that reduce their risk.

On the other hand, we know that it’s not as simple as just knowing what to eat and what to do in the gym. Excessive dieting or demonising certain foods as ‘bad’ can also sometimes damage people’s relationship with food, in some cases leaving them with eating disorders that make it even harder to lose weight.

Clearly, addressing obesity needs to be handled sensitively and needs to be based on dialogue about the needs of the intended audience. This applies not only to awareness campaigns but also to the government and healthcare professionals – the BPS report calls for government to ensure all initiatives promoting a healthy weight are informed by psychological research, and that healthcare professionals working in obesity services should have training on the psychology of obesity.

Whatever the right answer, you can be sure communication will be at the heart of it.

By Helena S.